Ancient churches are the greatest glory of Europe’s cities, and a headache for those trying to look after them

Erasmus | Apr 16th 2019

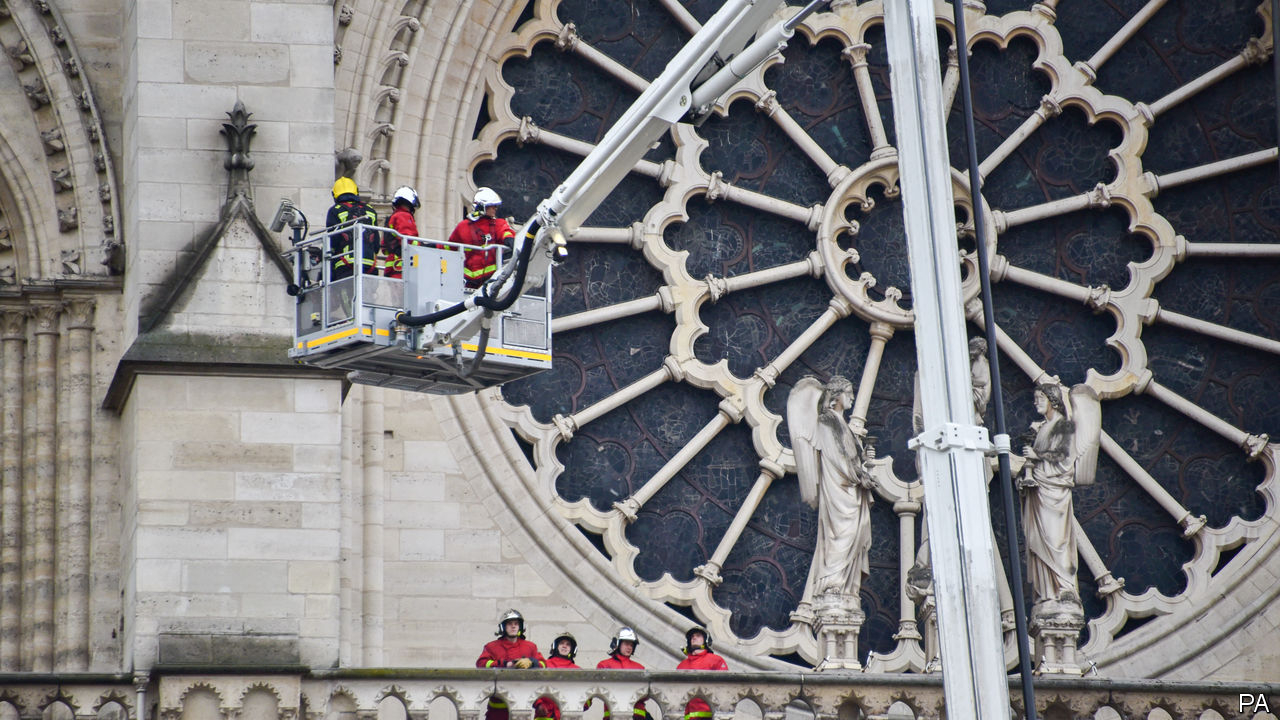

THE CATHEDRAL of Notre Dame in Paris, and the vast outpouring of sorrow over its semi-destruction by fire on April 15th, epitomises the power of great houses of prayer to touch and inspire people. More palpably than any other kind of monument, they connect visitors with another world: one in which the finest composers, singers, sculptors, glass-makers, embroiderers and craft-workers of a given era joyfully mixed their energies in a vast, disinterested enterprise.

To some degree, that enterprise continues as long as the building stands. That alone makes great historic churches a source of fascination, even for those with little interest in Christian worship. People want them to be there, even if they don’t wish to share the cost or join the prayers.

In almost every country in Europe, that creates an acute problem. The cost of maintaining the delicate stone fabric of a cathedral seems to rise geometrically, far out-stripping the ability of small congregations to sustain them. Governments and other secular bodies are minded to help but they also feel compelled, in most places, to respect the independence of the buildings’ historic stewards, in other words the churches.

In England, the established church boasts 42 cathedrals (technically defined as the seat of a bishop), of which 39 are listed as historic buildings whose preservation is both mandated by law and entitled to some public help. (About 12,000 of the 16,000 other places of worship controlled by the Church of England are also listed.)

The Church of England likes to call the cathedrals one of its “success stories” with rising numbers of worshippers and visitors, and growing revenue. But as a recent report led by a bishop delicately put it, “recent failures of governance and management within a small number of cathedrals have highlighted vulnerabilities across the sector…” In plain language, at least two cathedrals have run into severe financial difficulties, which better stewardship might have avoided.

English cathedrals are relatively independent bodies, run by a cleric known as a dean who relies on a group of advisers known as a chapter. They are free to raise money in many ways, from concerts to exhibitions to simply charging an admission fee, as about a quarter of them do. In recent weeks Derby Cathedral raised eyebrows by hosting films that included graphic sex scenes and depictions of paganism.

Churches in Germany have an advantage. The system of religious taxes (under which people of Catholic or Lutheran heritage pay a levy to their respective denominations) has ensured an ample income stream. Germany’s religious masters have done better at hauling in revenue than at retaining worshippers, the figures would suggest.

But a massive fund-raising effort, drawing in generous private-sector donors and ordinary well-wishers in Germany and Britain, was needed for one of the biggest church reconstruction projects of modern times: the rebuilding of the Frauenkirche in Dresden.

This showpiece of German Baroque was destroyed, along with much of the city, in a British bombing raid in February 1945. The project, completed in 2005, was a complement to the erection in 1962 of a new cathedral in Coventry, replacing the one wrecked by a German air raid on the English Midlands.

Most European states subsidise their historically dominant Christian denominations, directly or indirectly, while also leaving the sects’ religious masters relatively autonomous. In Italy, despite the notional separation of Catholic church and state, the two are deeply intertwined, through tax breaks and state help for maintaining the artistic heritage which is one of Italy’s greatest tourist draws. Belgium offers generous help to all its main religions, but Catholic cathedrals still charge stiff admission fees as though they were museums.

In church-state relations, France is an outlier. Under the regime of laïcité, or strict secularism, municipalities took over formal responsibility for Catholic churches; clerics and their congregations are merely users. And clerics, in particular, are thin on the ground. In rural France, it is common for a priest to look after 30 old churches.

That paucity of active users prompts municipal authorities to assign a low priority to conserving church buildings. In 2013 a huge neo-Gothic church in the northern French town of Abbeville was dramatically demolished by municipal leaders, who said the place was a safety hazard and too expensive to repair. Hundreds of other French churches may soon have a similar fate. Nor have France’s state authorities done very well at protecting houses of prayer from a wave of vandalism, including arson and desecration, that has afflicted them this year.

Indeed, all over western Europe, churches are closing for lack of worshippers. In the Netherlands, a cardinal predicted in 2013 that two-thirds of the Roman Catholic churches in the country would shut by 2025.

But a diametrically opposing trend is at work further east in Europe. Perhaps the most spectacular act of church reconstruction of recent times was the re-erection of Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, which was dynamited by Stalin in 1931 and thrown back up over five years starting in 1995. It was rebuilt in about a tenth of the time needed for the original construction.

Elsewhere in Russia, under a crash building programme decreed by the Russian Orthodox church, at least three new churches are said to be opening per day. And in other parts of central and eastern Europe, from Serbia to Georgia, vast new Orthodox churches now adorn capital cities which were already endowed with many places of prayer.

Indeed, the Russian church building spree extends far beyond the borders of the motherland. Anyone who takes a short walk along the banks of the Seine from the wreckage of Notre Dame will soon see a boldly modernistic structure, topped with onion domes: this “spiritual and cultural” centre, opened in 2016, was a pet project of President Vladimir Putin’s. It competes hard with an older Russian-style cathedral in Paris which the Muscovite authorities, to their frustration, do not control.

As the Russian state media were eager to point out, western Europe is gaining some new Christian places of worship even as many others are destroyed, accidentally or otherwise.

See alsoA terrible blaze devastates Notre Dame cathedral (April 15th 2019)